In my previous post, I talked about present bias and psychological distance, and how the physics of psychological space warp our estimation of the value of things that feel far off. In this post, I’ll talk about how you can use the laws of psychological distance to your advantage.

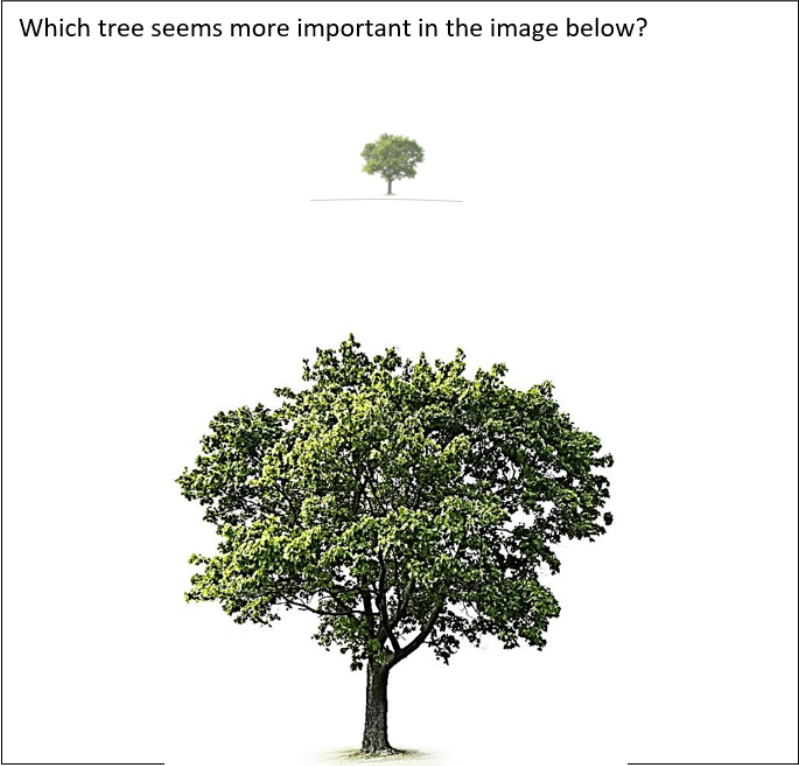

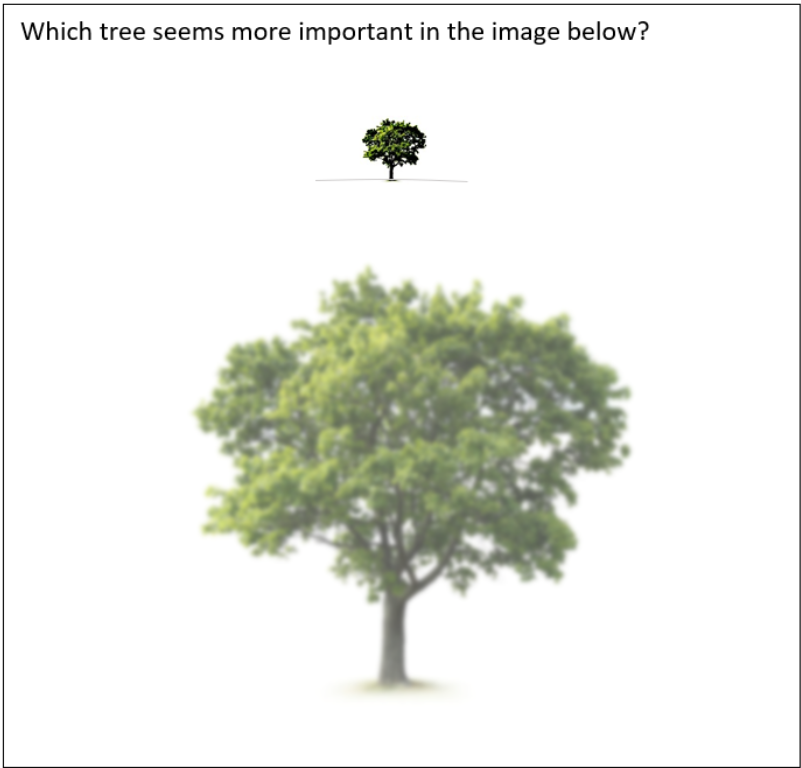

I gave the example of a landscape painting, where things in the foreground appear large and clear, and things in the background are smaller and fuzzier, with far less detail. That’s the way we naturally depict things in psychological space: Things that feel close take up more mental space and involve more detail, while things that feel far off are fuzzier, less formed, and contain fewer details. The technical term for this is construal level. High levels of construal are fuzzy and focus on the gist rather than the detail (while high-level takes the 1,000-foot view). Low levels of construal are clear and detailed as if looking at an object or event up close.

Now imagine that landscape, but instead of the foreground being in-focus and the background fuzzy, imagine that it’s the far-off that is in focus and the close-up that’s blurred. When you look at that scene, where does your attention go? To the background, naturally. The clarity of the imagery tells your brain to focus on that area.

Visual artists use these tricks of perspective to guide a viewer’s attention. It turns out we can do a similar thing, mentally, to counter present bias.

The Good News

Researchers have found that the relationship between psychological distance and construal level is bidirectional, meaning that if you change one, the other changes as well. In other words, if you add detail to your mental picture of something, it will feelcloser, psychologically. Likewise, if you blur or shrink your mental picture, it will feel further off.

Adding details to your picture of the future can make that future feel closer, more likely, and more important than it did when it was a blur on the distant horizon. That can offset some of the effect of present bias. There’s a case to be made for doing the opposite, too: mentally conjuring closer outcomes as if they were far off. I’ll give you a couple of examples.

UCLA professor Hal Hershfield and his colleagues have been studying the effects of psychological distance on savings. They have run experiments using MRIs, augmented reality, and age-progression software to study how thinking about our future-self can affect behavior. Evidence is piling up that suggests that the closer you feel to your future self, the more likely you are to make good long-term financial decisions.

For example, students who interacted with an age-progressed avatar of themselves had stronger saving intentions afterward than those who saw an avatar of their current self. I believe this experiment worked because seeing your own face aged in great detail shrinks the psychological distance between who you are today and who you imagine you will be in the future. When the picture of your future is close-up, detailed, and clear, you can’t wave it away as easily as you can a far-off, vague image of an abstract idea like “retirement” or “old age.” By forcing a close, detailed view of your future, you impose a low-level construal, which your brain interprets as real, likely, and important.

Here’s another trick: Imagine your future in first-person. See out through the eyes of your future self, rather than imagining your future from the outside looking in. This trick of perspective helps reduce psychological distance, too. See it up close, in detail, and through your own eyes, and it will likely feel closer, more important, and you will naturally care about it more. This can offset the effects of present bias.

The Reverse Can Help, Too

You likely know what it’s like to be “too close” to something to be objective. We talk often about putting distance between ourselves and a difficult problem in order to gain a better perspective. When emotions run high, we tend to make decisions with a “hot head” instead of calmly considering our options. It turns out, there’s a simple but effective mental trick to get perspective quickly: Talk to yourself in the third person. I know. It’s weird.

Imagine you’re upset with a colleague. They have stepped on your nerves for the last time. You’re hot around the collar and ready to have it out. Instead of thinking, “I am hopping mad, and totally justified in telling them off,” you would say to yourself, “Matt,” (your name is Matt now), “Matt is hopping mad and thinks he’s justified in telling his colleague off.” That little shift in perspective from first to third person puts a sliver of psychological distance between you and your angry self, allowing for just a bit more objectivity on the situation.

What Does This Have To Do with Investing?

Everything. Investing is emotional. There are the highs of great returns, the lows of losing, and all the emotions that go along with trying to choose where to put your money. We try to make it more rational, but we can’t really escape the fact that what happens to our money happens to us.

So, whether you are antsy to get in on bitcoin or a long-awaited IPO, reeling from a serious loss that set you back a year, or impatient to see returns faster than those boring (but smart) exchange-traded funds will give you, psychological distance is playing a part in your mental cost-benefit analysis and you would be wise to use it to your advantage rather than let it lead you into a trap.

The Bottom Line

Perspective is not reality when it comes to weighing options, so be careful. Present bias magnifies the importance of the immediate when compared with the future, and it leads plenty of brilliant folks unwittingly down the wrong path. Learning to see the close-up through a third-person perspective can help you respond more coolly to otherwise emotionally heated situations. Likewise, bringing the far-off closer in your mind’s eye, adding detail and seeing it through a first-person perspective can help you weigh the future more accurately.

Our brains are amazing computing machines, but the physics of psychological space warps our ability to correctly view alternatives if they take place at different times. Training your mind’s eye is not easy, but it is a simple way to make much better decisions for the long-run, and your future self will thank you when your financial dreams are realized.

This post by Sarah Newcomb was first published on Morningstar.com